-

Private Equity

Private equity and venture capital managers

-

Credit

Private debt, CLOs, and public credit

-

Fund Administrators

Fund administrators serving private capital

Back Office

Investor Relations

Investment Management

Enterprise Data Solutions

Front Office

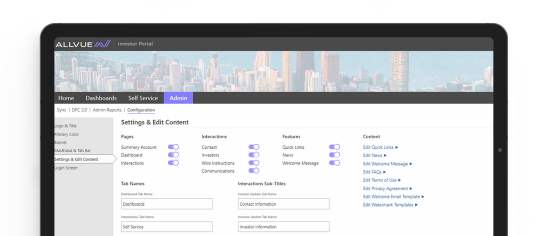

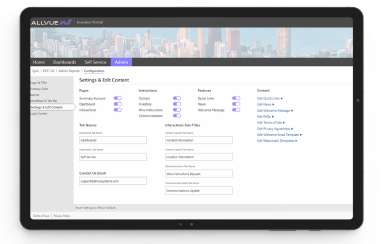

Investor Relations

Back Office

Technology Partner

Enterprise Data Solutions

Back Office

Enterprise Data Solutions

Investor Relations

Data Collection

Purpose-built for your investment strategy and fund lifecycle

Investment Strategy

Emerging Managers

Diversified Managers

Allvue monthly newsletter

Sign up to receive regular updates on Allvue's content, award wins, product releases, and more.

Allvue monthly newsletter

Sign up to receive regular updates on Allvue's content, award wins, product releases, and more.

- BACK

- Private Equity

- Back Office

- Investor Relations

- Investment Management

- Enterprise Data Solutions

- REQUEST A DEMO

- BACK

- Credit

- Front Office

- Investor Relations

- Back Office

- Technology Partner

- Enterprise Data Solutions

- REQUEST A DEMO

- BACK

- Fund Administrators

- Back Office

- Enterprise Data Solutions

- Investor Relations

- Data Collection

- REQUEST A DEMO

- BACK

- Who We Serve

-

- Private equity

- Venture capital

- Private debt

- CLOs

- Fund of funds

Investment Strategy

- Private equity

- Venture capital

- Private debt

- Fund administration

Emerging Managers

- Credit Research Solutions

Diversified Managers

-

Purpose-built for

your investment strategy and fund lifecycle - REQUEST A DEMO

- BACK

- Resources

-

Allvue monthly newsletter

Sign up to receive regular updates on Allvue's content, award wins, product releases, and more.

- REQUEST A DEMO

- BACK

- Company

-

- Agentic AI Platform

NEW

Allvue AI

- Nexius Data Platform

Data Management

-

Allvue monthly newsletter

Sign up to receive regular updates on Allvue's content, award wins, product releases, and more.

- REQUEST A DEMO