By: Philitsa Hanson

Head of Product Management

August 14, 2025

A Drive Through Window on a Michelin Star Restaurant

Picture a Michelin star restaurant installing a drive-through window for grab and go service instead of their usual approach of meticulous design and refined ambiance with elegant lighting, luxurious materials, and artful table settings. Meals at Michelin-starred restaurants are artfully crafted culinary experiences, showcasing exceptional ingredients, precise technique, and artistic presentation that balance flavor, texture, and innovation. The drive through menu still features truffle risotto and 12-hour braised short ribs, but the new window promises instant service to customers used to grabbing a combo meal in under five minutes. The result: disappointed customers, stressed staff, and a kitchen struggling to reconcile two completely different service models.

That’s the reality we face with the recent Executive Order enabling private equity, private credit, and other alternative assets in 401(k) plans. The intent is to democratize access by giving 90 million American retirement savers a taste of the diversification and return potential long enjoyed by pension funds and institutional investors. But in practice, it’s asking a system designed for daily liquidity, transparent pricing, and ultra-low fees to suddenly process assets that are illiquid, opaque, and operationally complex.

The Policy Shift

The Executive Order directs the Department of Labor and the SEC to re-evaluate fiduciary guidance under ERISA, consider new safe harbors, and potentially relax rules around accredited investor status. Supporters say this will level the playing field, letting ordinary savers access strategies traditionally reserved for public pension funds and endowments.

It’s an ambitious vision. But like bolting that drive-through window to a fine dining kitchen, the policy change doesn’t address the infrastructure overhaul needed to make it work.

401k and Private Market Investments: The Operational Mismatch

It’s worth noting that 401(k)s aren’t entirely strangers to assets that don’t price daily. For example, some target date funds can include a small slice of illiquid assets, like private equity, even if the broader fund reports daily. And CITs pool assets outside the mutual fund structure, sometimes holding alternative investments with periodic valuations.

These structures prove that non-daily valuation can coexist in a 401(k) but only under very controlled circumstances. They rely on buffers, blended valuations, and liquidity management techniques to prevent valuation lags from disrupting participant transactions. Importantly, their illiquid components are typically modest in size and embedded within vehicles designed to absorb the operational complexity behind the scenes.

Direct investment in alternative assets expose operational mismatches that need to be addressed. Participants expect to be able to move money between funds at will. Private equity, for example, has multi-year lockups, capital calls, and staged distributions. Without fundamental changes, plan sponsors will face awkward workarounds, the financial equivalent of handing out IOUs at the pick-up window. The average mutual fund in a 401(k) charges about 0.30% annually. Private funds routinely charge “2 and 20” plus portfolio expenses buried in footnotes. Translating these into clear disclosures that are participant-friendly is like squeezing a ten-course tasting menu onto a drive-through receipt. In public markets, price movements are visible and tied to familiar headlines. In private markets, performance updates are infrequent and sometimes counterintuitive. That disconnect can erode trust when participants expect to see direct outcomes of their investments.

The Fiduciary Tightrope

Even with the Executive Order’s promise of safe harbors, plan sponsors face a delicate balancing act. There are many cases of employees suing their employers over alternative assets in retirement plans, – Intel being a more recent and public one. Fiduciary defense in this space can drag on for years and rack up millions in legal fees. The risk isn’t just about market losses; it’s about whether the menu is appropriate for the clientele, whether the pricing is fair, and whether the customers truly understand what they ordered.

In restaurant terms, it’s one thing to serve a complicated, slow-prep dish to a table that booked months in advance and knows what to expect. It’s quite another to slide it across a drive-through window to someone who assumed they were getting a combo meal and then is surprised when the experience connected with consuming it doesn’t align with their expectations. In other words, it took too long to deliver, costs more than what they are used to paying, or doesn’t taste like anything they’ve had before.

For plan fiduciaries, every mismatch in expectations becomes a potential point of liability:

- Performance – Participants accustomed to transparent, daily-priced assets may view valuation delays as concealment.

- Fees – Even well-structured private market products will carry costs that look excessive next to index funds.

- Suitability – A fund appropriate for a long-term investor in theory can still be deemed unsuitable if presented without adequate education and context.

Without rigorous product vetting, crystal-clear disclosures, and participant education that goes beyond a single brochure, the restaurant’s “special of the day” could turn into a legal migraine. Safe harbors might reduce the heat in the kitchen, but they won’t eliminate it, especially if the patrons weren’t prepared for the meal they ordered.

What Must Change For Private Assets and 401ks to Coexist

If private assets are to coexist successfully within 401(k)s, three operational shifts are critical. First, product innovation must produce structures with periodic liquidity, simplified fee models, and hybrid valuation approaches — much like the way stable value funds manage crediting rates but tailored for the realities of private markets.

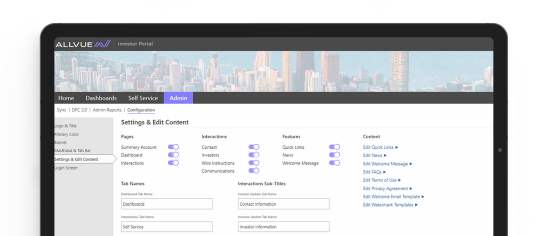

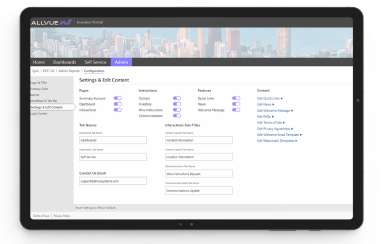

Second, the operational backbones of the 401(k) and private asset systems must be modernized. This means building the capability to integrate illiquid, infrequently priced investments into daily recordkeeping and reporting environments with strong controls for valuation timing, cash flow tracking, and participant transaction processing. It’s the equivalent of renovating the kitchen so it can handle both the speed of drive-through orders and the precision of multi-course fine dining. Here, technology that can unify investment and fund accounting, automate complex workflows, and reconcile across multiple data sources can ensure the kitchen runs smoothly even with a complex menu. Achieving that requires a data environment – such as with Allvue’s Nexius solution – capable of aggregating and reconciling information across multiple asset classes, structures, and systems. Solutions like Nexius can provide that unifying layer to give plan sponsors and managers a single source of truth that connects public and private market data seamlessly.

Finally, large-scale investor education must be prioritized, ensuring that participants understand not just what they own, but how it’s valued, why it behaves differently from public assets, and what that means for their retirement strategy. This kind of investor education is not currently standard with 401(k) plans and is something that should be embarked upon jointly between plan providers, private asset managers, and plan sponsors.

Without these three changes working in concert, the risks of confusion, frustration, and fiduciary exposure will remain far greater than the potential rewards.

Do Private Market Assets Belong in Long-term Retirement Portfolios

Private assets can belong in long-term retirement portfolios and there’s precedent for blending non-daily assets into a daily-valued system. But the examples we have today are controlled, limited, and purpose-built to smooth over valuation and liquidity gaps.

Bringing large-scale private equity and private credit into 401(k)s without similarly thoughtful design creates the risks of long lines, frustrated customers, and a product that no longer delivers on its promise. Otherwise, we’re just serving 12-hour braised short ribs through a drive-through window and pretending that it offers the same multi-faceted experience as dining in.

Learn more about Allvue’s Nexius data platform or request a demo here.

More About The Author

Philitsa Hanson

Head of Product Management

Philitsa Hanson is Allvue's Head of Product for Equity and Fund Administration where she oversees product strategy and delivery for private equity and accounting solutions. For over 20 years, she has architected and launched front-to-back platforms across capital markets, spanning order management, investment accounting, fund accounting, and consolidated back-office workflows. Philitsa has led large-scale transformational change programs at global firms to drive end-to-end operational excellence. A respected voice in the industry, Philitsa speaks on operational improvements and collaborates with advisory boards to help shape the future of capital markets.